Edward Carpenter, The story of Eros and Psyche, 1900

Facets of Apuleius’ Golden Ass in the Brotherton Collection at Leeds

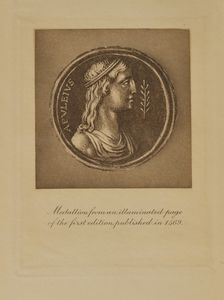

Apuleius, Opera, 1588

Philander, The Golden Calf, 1749

Voltaire, La Pucelle d'Orleans, 1762

William Adlington, Cupid and Psyche, 1903

Harold Edgeworth Butler, Cupid and Psyche, 1922

Boccaccio, 1511

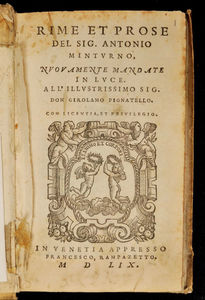

Minturno, 1559

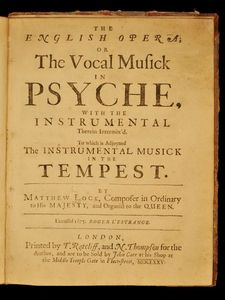

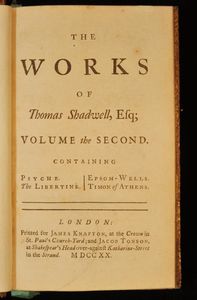

Thomas Shadwell, Psyche, 1675

Thomas Shadwell, Psyche, 1675 (2)

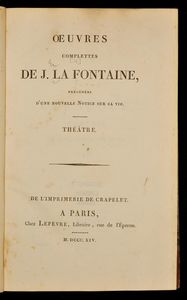

Jean de la Fontaine, Les Amours de Psyché et de Cupidon, 1814

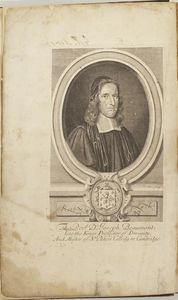

Joseph Beaumont, Psyche, or love's mystery, 1702

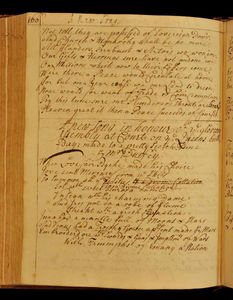

Thomas D'Urfey, A new song in honour of the glorious assembly at Court on the Queens birthday

Mary Tighe, Psyche or The legend of love, 1812

Christoph Wieland, Fragments of Psyche, 1767

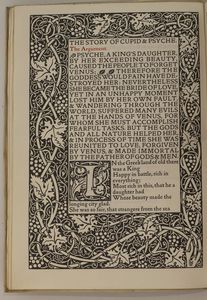

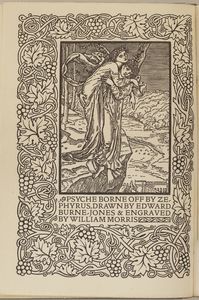

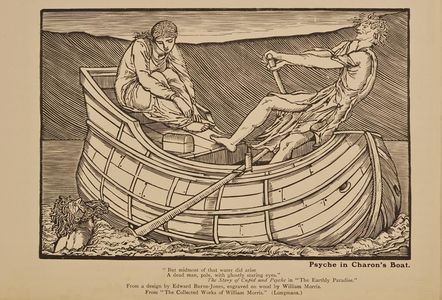

William Morris, The earthly paradise, 1868-70

A note by William Morris on his aims in founding the Kelmscott Press, 1898

William Morris collected by Alf Mattison

Robert Bridges, Eros and Psyche, 1885

Victor de Laprade, Psyché, 1857

Edward Carpenter, The story of Eros and Psyche, 1900

Walter Pater, Marius the Epicurean, 1885

Georges Jean-Aubry and Manuel de Falla, Psyché : poème, 1927

Pierre Louÿs, Psyché, 1927

Edward Carpenter (1844-1929) was a poet and socialist, his friends include, among others, Walt Whitman, William Morris (with whom he joined the Socialist League), and Tagore. He was attracted to men and allegedly inspired E.M. Foster’s Maurice. In the 1870s he moved to Yorkshire, intending to bring education to the deprived areas of Northern England.

In this edition, Eros and Psyche is paired with a translation of Homer’s Iliad 1 into hexameters. The introductory note describes the Greeks as barbarians and uncivilised, and draws repeated comparisons of the Greeks with North American Indians or Zulus, in their nature, use of weaponry, and dietary habits. In his treatment of Apuleius’ text, Carpenter freely adapts and admits to changes, but he carefully indicates with diacritic signs in his translation of Homer where the requirements of the English verse translation made him add or omit words.

Carpenter sees the story of Eros and Psyche primarily as a fairy tale – he compares it with Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty. As he wrongly thinks there were Greek versions of the story which inspired Apuleius, he uses Greek instead of Latin names for the gods (hence Eros instead of Cupid), and simplifies the story. He is worried about Aphrodite (Venus), whose “undignified” behaviour he blames on Apuleius alone.

He adjusts the text to match the fairy tale interpretation. Eros is more like a prince, who after his recovery from the wound has “grown, even by what had happened, to greater glory and manhood than before” (p. 43). Just like Tighe, Carpenter makes much of Cupid’s first sight of Psyche – in Apuleius we hear about this voluntary wounding and falling in love much later, Carpenter tells the story chronologically (p. 13).

Like many before and after him, he tries to individualise and distinguish the two sisters of Psyche, something that Apuleius does not do. He also lessens Psyche’s involvement in their deaths: “But Psyche’s eldest sister meanwhile, hearing a vague report of what had happened – and of Psyche’s exile from her enchanted palace – and being seized with envious desire and maddening lust to obtain all these riches and the embraces of a god, conceived the idea of supplanting Psyche” (p. 32). Both she and her sister perish at the bottom of the rock, and the author comments: “And thus these two, dashed to death at the foot of the rocks, met with the fitting reward of their treachery.”