Queering the Medieval

Queering the Medieval

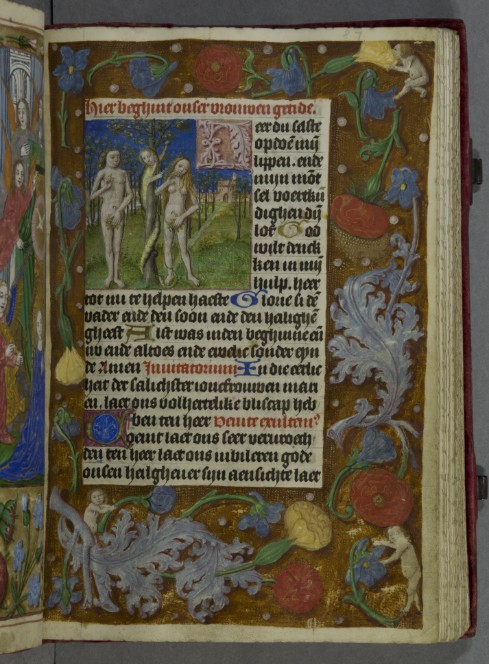

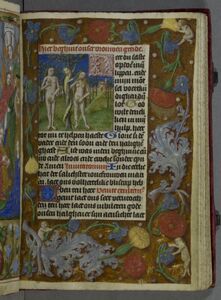

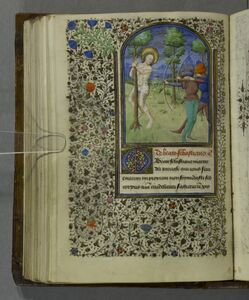

This Research Spotlight investigates the glimpses of LGBTQ+ narratives from the Middle Ages within the holdings of the university’s Cultural Collections. It traverses medieval manuscripts, stories, poetry and the lives of saints and historical figures. Written by LGBTQ+ intern Rosaleen Williams, MA Art Gallery and Museum Studies.

A period roughly spanning from the end of the Roman Empire to the beginning of the Renaissance (5th – 15th century), the medieval era encompasses a variety of different societies and geographical regions, which across time, have all produced individual cultural practices. We generally tend to think of this period as concerned with the morality of Christianity and church tradition, as well as the assumed gender roles of marriage. However, people did have sex, outside of marriage, for pleasure and with people of their same gender. Through the archival record, it is easier to derive behaviours of monarchs, or ascertain the tales of writers, but there is unfortunately little in the historical record of the lives of ordinary people. Although, archival sources can provide a fruitful dialogue in relation to how medieval people viewed relationships. We may also uncover contemporary behaviours by way of examining their prohibition, in sources such as penitential prayers. Through studying medieval ideas of love, sexuality and gender, it is possible to get a glimpse at the views and behaviours of ordinary people from the Middle Ages.

Judith Bennett writes that before 1500, archives encounter silence, especially regarding women and lesbian sexuality [1]. It is theorised that this is possibly because female same-sex relationships were seemingly devoid of male genitalia and were perhaps not considered ‘sexual’, therefore being ignored or not recorded. Male homosexuality has been evidenced by records on criminality, in reference to acts of ‘sodomy’, or in books written about legal and moral codes of the time. There are few sources in the way of transgender individuals, although we do know that people existed outside of traditional gender binaries, such as Eleanor Rykener (late 14th century). Because little information on sexuality in general was recorded, archival records must be used in new and inventive ways, to create a history of sexuality without the depiction of sexual acts [2]. This means that the possibilities of queerness amidst coded language must be considered, where allusions of sexuality and gender nonconformity have possibly been presented. It is why the imaginative nature of stories and poetry can be helpful in sourcing narratives beyond heteronormative binaries.

When ‘queering’ the medieval, it is also important to consider the use of language. The terminology within the LGBTQ+ acronym includes words mainly coined in the 20th century, which would not have been in use in the medieval era. The term ‘Queer’ can be helpful in application to behaviour that may not directly align with modern day descriptors, but defies or subverts contemporary societal convention. ‘Queer’ is therefore any sex that exists outside of the ‘norm’, of which is not constant.

There are behaviours in archival records that LGBTQ+ communities today can indeed relate to, or there are figures that have now become icons for communities, irrespective of historical sources of their behaviour. The study of archival material and the writing of history accounts in part to representation. In the words of Anna Klosovwka, ‘all fiction corresponds to an absolute reality-not of existence, but of desire that calls fiction into being, performed by the authors and manuscript makers; and continuing desire for it performed by the readers, a desire that sustains the book’s material presence across the centuries' [3]. How history is interpretated overtime is just a part of the formation and writing of the past, for the historical record is constantly shifting based on the present. By examining a Queer history of the Middle Ages, it reveals that normative heterosexuality has always been the outcome of construction.

Queer history involves subverting narratives of progress and development, which might involve examining sections of the past that may not first present as containing Queer narratives [4]. The medieval era has often been a neglected site of Queer historical studies, with a Queer historiography revolving around ideas of modern development, which emphasizes the ancient worlds of Greece and Rome, to the Early Modern period and 20th century. During the 1980s, a surge of Queer theory in application to the Middle Ages emerged, evolving from traditions of writers such as John Boswell. This Research Spotlight aims to traverse Cultural Collections for clues of queerness in the archival record, incorporating queer theorists and medievalist writers to examine manuscripts, stories, poetry and the lives of saints and historical figures.

[1] Judith Bennett, ‘‘Lesbian-Like’ and the Social History of Lesbianisms’, Journal of the History of Sexuality, 9 (2000), 1-24 (p.3).

[2] Anna Klosowska, Queer Love in the Middle Ages (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), p.10.

[3] Klosowska, p.7.

[4] Glenn Burger, Steven Kruger, ‘Introduction’, in Queering the Middle Ages, ed. by Glenn Burger, Steven Kruger (Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2001), p. XIII.

© Copyright University of Leeds

![CC.5705 [1]](https://explore.library.leeds.ac.uk/multimedia/78736/655451_001%20x.600x300.jpg)