Medieval Manuscripts and Saints

Cultural Collections contains a large amount of medieval manuscripts, consisting of the Brotherton Collection Manuscripts, Special Collections Manuscripts and Ripon Cathedral Medieval Manuscripts, as well as over 300 incunabula (books printed in Europe before 1501). Like theological works that condemn particular sexual acts, many items in Cultural Collections' Medieval Manuscript collection contain penitential psalms, such as the Beverley Prayer Book (BC MS 16). These penitential writings often showcase the sinful concerns of priests, ultimately demonstrating that nonconforming sexuality was occurring.

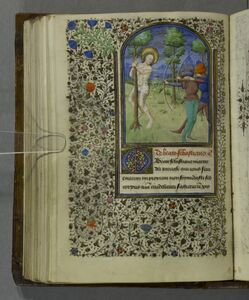

During the later medieval era, Christian devotion was focused on individual prayer and relationships to Christ. As such, images of Jesus and his side wound, incorporated aspects of femininity, masculinity and aspects that signify as neither [5]. This allowed viewers to relate to Christ’s suffering on a greater intimate level, for the body was recognizable to all people. These images appeared in Books of Hours across medieval Europe, of which Cultural Collections holds several, an example being Horae Beatae Mariae Virginis (BC MS 3). Devotion was also encouraged to utilise all human senses, so depictions of side wounds in manuscripts were encouraged to be kissed. Sophie Sexon argues that this opened erotic possibilities, particularly for women [6].

Cultural Collections holds a 13th century manuscript (Ripon Cathedral MS 2) from the Ripon Cathedral Collection by Saint Anselm (1033-1109), who wrote homoromantic letters to male friends. As Archbishop of Canterbury, Anselm also blocked legislation which would define homosexuality as a sin, advocating for counselling rather than punishment. Another manuscript compiled in the 13th century, known as The Golden Legend (BC GB C16/17/JAC), details the story of Saint Eugenia. Eugenia lived for a period time as a male monk, who then was placed on trial and forced to reveal the ‘true’ identity of being woman.

Eugenia is part of a tradition of saints that chose to cross-dress for piety and religious devotion, interestingly combing orthodox religion with non-orthodox behaviour [7]. Some writers have discussed the possibility that in medieval society, gender transformation was seen as holy, in the sense that being outside of earthly binaries brought these figures closer to God [8]. These narratives of cross-dressing saints perhaps reveal a more complex medieval understanding of sexuality and gender.

Many medieval manuscripts contain beautiful illustrations of saints, who often had lives that could be interpretated through a queer lens. Saint Augustine (354-430), depicted in a c.1500 Prayer Book (BC MS 12/22) in the archives, wrote on the ‘sinful’ nature of pleasure in the 3rd century. However, Augustine did discuss his own sexuality and attraction to men in the work Confessions (Ripon Cathedral Library I.B.28), while also believing that God created intersex people.

Saint Sebastian (c.256-287) is also depicted in this Prayer Book, as well as a Book of Hours (BC MS 4/27) from 1450-1475. During the later medieval period and Renaissance, Sebastian became a popular subject of art. Often, he would be depicted bare chested, tied to a tree and pierced with arrows that seemingly show him experiencing a form of spiritual pleasure and pain. It is perhaps through these semi-erotic portrayals, that Sebastian became a figure of intrigue for 19th century gay, male communities. His torture resonated to feelings of persecution and shame within society. Within the 20th century, Sebastian was further celebrated as a gay icon, especially amidst the AIDS epidemic, as he is also considered a figure who protects against disease.

Cultural Collections contains a 17th century copy of the works of Saint Aelred of Rievaulx (All Souls Theology 3 AEL). Aelred was an abbot at Rievaulx Abbey, a Cistercian monastery in North Yorkshire in the 12th century. Focusing often on the theology of friendship, Aelred encouraged friendships and public affection amongst his monks, as well as seemingly having lifelong ‘friendships’ with other men.

The collections contain many books that detail the life of Joan of Arc, including one from 1612 (BC For C17/18/HOR) and a 20th century work about her trial (BC Read D4083). Living in the 15th century, Joan defied traditional gender expectations, as she cut her hair short and engaged in cross-dressing. Joan was so resolute in her beliefs, most of all that she was receiving divine revelations, that she was burned at the stake for heresy. During her trial, she was also accused of the offences of wearing men’s clothing and witchcraft.

Another 20th century collection item referencing medieval saints is the Passion of SS. Perpetua and Felicity (BC Read D1053). This work, originally written by Saint Augustine, details the story of these two women. Perpetua and Felicity lived at the end of the 2nd century and were martyred for their faith, embracing each other in a kiss before their death.

There is no direct evidence about how any of these saints identified in a particular way, but many of these figures have become icons for LGBTQ+ communities. In taking a queer approach to archival research, it is important to consider how history can be used as a source of representation, in which people now can resonate with themes, identities and behaviours. How we interpret history overtime is just a part of the formation and writing of our past.

[5] Sophie Sexon, ‘Gender-Querying Christ’s Wounds: A Non-Binary Interpretation of Christ’s Body in Late Medieval Imagery’, Trans and Genderqueer Subjects in Medieval Hagiography, (2021), 133-154 (p.134).

[6] Sexon, p.134.

[7] Amy Ogden, ‘St Eufrosine’s Invitation to Gender Transgression’, Trans and Genderqueer Subjects in Medieval Hagiography, (2021), 201-222 (p.202).

[8] Alicia Spencer-Hall, Blake Gutt, ‘Introduction’ in Trans and Genderqueer Subjects in Medieval Hagiography, ed. by Alicia Spencer-Hall, Blake Gutt (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2021), pp. 11-40 (p.14).

© Copyright University of Leeds

![CC.5705 [1]](https://explore.library.leeds.ac.uk/multimedia/78736/655451_001.thumb.jpg)