How Did Medieval People View Sexuality and Gender?

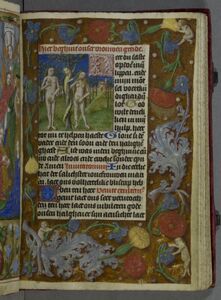

In Europe, the Christian church portrayed sex as an act only acceptable for the purpose of procreation. Marriage was also an important element of medieval life, referenced in works such as the 12th century book of catholic law, Decretum Gratiani (Ripon Cathedral Library XVII.H.9/q). In this work, passages condemn homosexuality, as well as non-marital sex. It was believed that in order for children to be conceived, men were to be the active agent and women to be passive. The word ‘Sodomy’ defined any sex that wasn’t for procreation, not necessarily specifically same-sex activity, so the term also applied to behaviour where a male was not active, or sex was outside of marriage. Therefore, medieval people did not differentiate sexuality in a modern sense, but were concerned more with this passive / active dichotomy and marital union. The term ‘Sodomy’ originates from the Biblical story of Sodom and Gomorrah, which is illustrated in a 1490 incunabula in Cultural Collections (BC Incunabula/ROL). Within medieval historical accounts, there is evidence that people and groups were punished at medieval inquisitions for the act of sodomy, such as the Knights Templar, who were disbanded in the 14th century partially on these grounds.

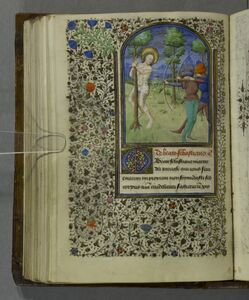

The writings of Galen (129-216) in the 2nd century, such as De Temperamenti (BC For C16/GAL), had resonating ideas in medieval society. In particular his ‘two seed’ theory, which assumed that both men and women needed to experience pleasure from sex, in order to conceive. Contemporary writers, such as the theologian Thomas Aquinas (c.1225-1274), wrote about the morality of sex. In the 13th century, Aquinas condemned homosexuality in Summa Theologica (BC For C16 quarto THO). Additionally, works such as Malleus Maleficarm (BC H de W/INS), written at the end of the medieval era, describe acts of witchcraft among women. Although these sources are damning of particular behaviours, they offer an historical understanding of activity that was taking place at the time. Further, Malleus Maleficarum is one of many sources which can be used in the construction of a ‘lesbian’ history, which intersects heavily with historical accusations of mysticism, heresy, and witchcraft.

Cultural Collections also contains works that openly discuss sex, such as the tale of Ableard and Heloise (INDEX/BCMSV/6684 Lt 119), originally from the 12th century. The tale is of a love affair that defies societal expectation but ultimately leads to both characters confined by the conventions of Christianity. Works such as Njal’s Saga (Icelandic F-2.1/NJAL [case]), an Icelandic saga written in the 13th century by an anonymous author, also explores themes of gender roles and societal expectation. Further, Cultural Collections hold works that discuss sex and same-sex desire more freely, particularly the 14th century work The Decameron (Strong Room for. 8vo 1552/BOC) by Giovanni Boccaccio. The Decameron is a collection of stories that openly explore themes of prohibited desire, sexuality and infidelity, such as in the tale of Pietro di Vinciolo.

The term ‘cross-dressing ‘or ‘hermaphrodite’ was used to describe people who were supposedly gender non-conforming, or who wore clothes outside of traditional gender roles. These terms also became tropes in literature and theatre. Neither necessarily conflate with modern day transgender or gender Queer identities, but it’s one of a few historical starting points in creating a medieval history that incorporates gender and sexuality. Other terms, such as eunuch, have associations with Queerness. ‘Eunuch’ was used to describe the modern term of intersex or a castrated male, presenting a dialogue of gender transformation, as well having medieval associations of ‘effeminate’ behaviour and same-sex preference.

© Copyright University of Leeds

![CC.5705 [1]](https://explore.library.leeds.ac.uk/multimedia/78736/655451_001.thumb.jpg)